Throwing a Block

Redefining SWAT as, Sacrifice, Work, Attitude and Team

Radio traffic breaks the sound of officers chatting. An in-progress call to a scene where a person in crisis is firing a rifle inside his house rings out for the team to hear. A cacophony of armor, ringtones and rifles clatters out the door as members of the Fort Collins Police Services Special Weapons and Tactics team race to the scene, leaving meetings, patrol and home behind.

The response unfolded much like a hostage situation the team responded to a while back. Officer Justin Burch responded to a situation where two adult women were held overnight at knifepoint by a 38-year-old man. Burch, stacked against the door with two other officers, entered the building, recovering both women and safely placing the man under arrest.

“Obviously, going through the door on a hostage situation — that's one of the riskiest things that we can do,” Burch said. “But we've trained for it.”

Working under pressure

Hostage situations are rare and dangerous occurrences that require a rapid and coordinated response from law enforcement. However, speed can lead to mistakes, as Sgt. Gar Haugo warned. “It causes you to think in a compressed timeframe,” he said. This can causally bring about the ability to switch between a tactical mindset and their innate emotional reactions.

“There is a lot of stimulation and excitement, but you're not really thinking a long way (out),” Haugo said. “(For example), 'What if I get shot and paralyzed today? Then what's going to happen? Who's going to take care of my kids?’ You're not thinking about those kinds of things.” Burch echoed this sentiment.

“It's more thinking through all the things that can happen and, 'What am I going to do if the hostage runs out the front door?'” Burch said. “'What am I going to do if the suspect comes out the front door with nothing in his hands? What am I going to do if he comes out the door with a gun in his hands?'"

To mitigate the risk both physically and emotionally, the team emphasizes working tactically and methodically through high-pressure situations. Guided by a safety priority system, the team directs their actions toward those who do not have the ability to leave the situation. This can lead to the employment of specialized equipment or a tactic known as "throwing a block." This technique involves members physically shielding a person from an attacker with their bodies, compounding the risk to themselves. This tactical approach has resulted in the team successfully completing 279 tactical call-outs over the past four years with no fatal encounters caused by officers, according to FCPS.

Managing mental health at work, home

Due to the highly stimulating environments officers engage with, the department provides resources like psychologists and encourages utilizing a network of fellow officers and family for further support.

“There used to be kind of a stigma against getting (that) sort of help or talking about things like that,” Burch said. “And I don't necessarily think that's a thing of the past everywhere, but I think it's kind of a thing of the past here, or at least we're working toward that.”

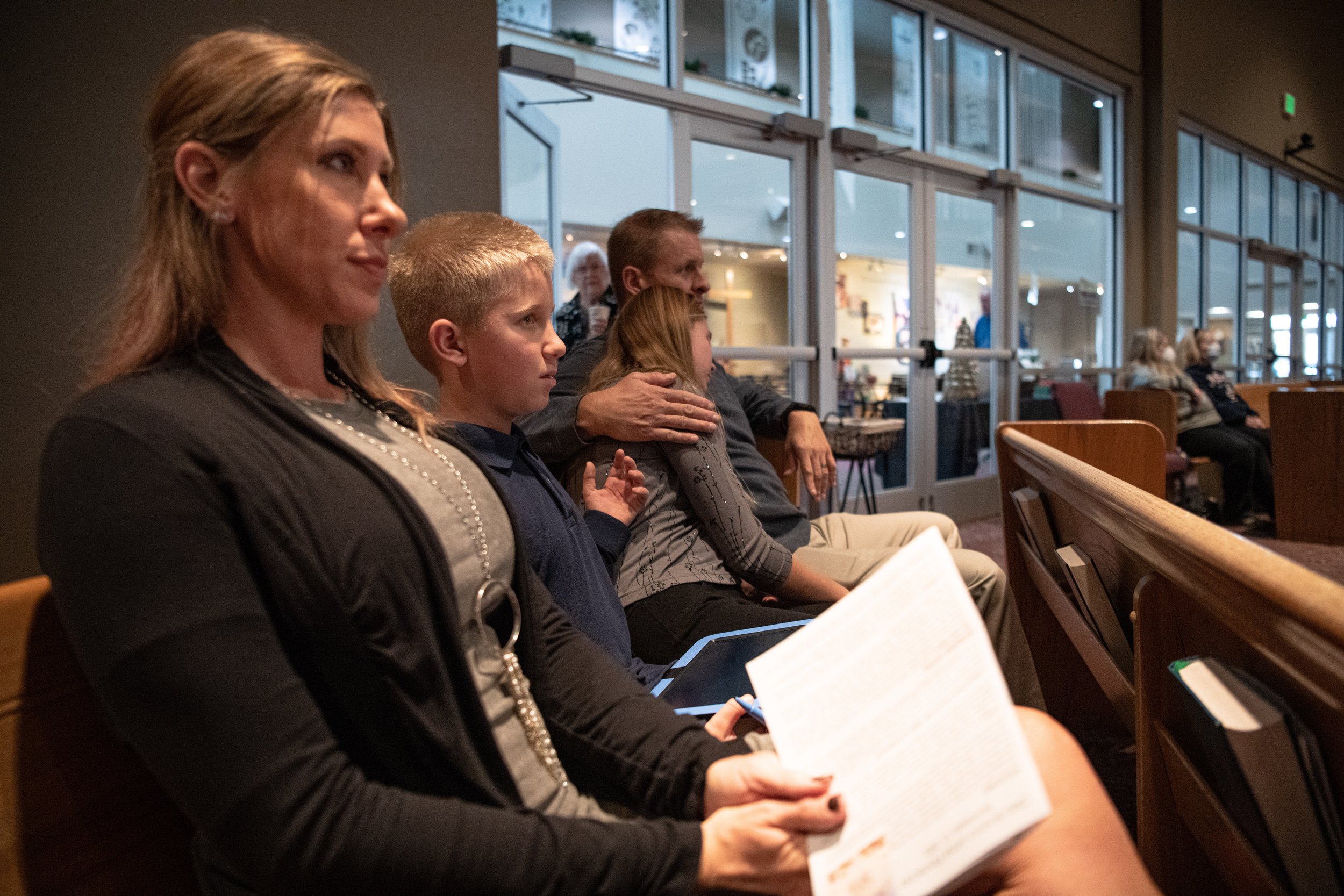

Some experiences follow officers home and continue to affect them, which prompts them to find ways to cope and heal with their families. Haugo found that discussing his work life with his family eased their concerns.

“Your kids are pretty adept at being able to read you,” Haugo said. “And so I will usually tell them, 'Hey, this is what happened. We went to a place, and this guy shot himself.’ And (my kids ask), 'Well, where did he shoot himself?' 'He shot himself in the mouth through his head.' And they're like, ‘Oh.’”

When sharing what he does, Haugo does not show his children gory photos, but he will discuss what happened and answer any questions they may have. It is a discussion many would find difficult to have with their children, but Haugo has found that it gives them more confidence about the world.

“I think sharing that with them is, for me, a way of telling them, ‘Hey, everything went okay,'” Haugo said. “‘The guys are alright.’”

His wife of 13 years, Amanda Haugo, was a patrol officer and detective before meeting Gar Haugo. Working mostly on sex crimes and patrol beats, Amanda Haugo said she has found she can relate to Gar Haugo’s work and appreciates his transparency. Even with the transparency and her ability to relate, some things are still difficult, especially when raising two kids.

“Sometimes I feel like work gets the best of him,” Amanda Haugo said. “And then we get what's left over when he comes home. Honestly, that part is hard sometimes.”

But on every call, she is proud of her husband and the team. “They would give their lives to protect people they don't know,” Amanda Haugo said. Fellow officer of eight years and father of three, August Barber, had discussions with his children as well. They have seen the media talk about police officers and picked up on things in school, both good and bad.

“Even though they hear these things, they know me as their father,” Barber said. “Obviously, they know what I've taught them, and if it doesn't line up with what they're hearing, then we just work through that.”

Over the years, Barber’s children have begun to understand what it is their father does and the dangers associated with the job.

“Those questions have come up (with my children) about, 'Do you always win?'” he said. “And we have had that conversation that we always try to win, but things happen.”

His children have seen their father injured and, further, other police officers’ funerals.

“I think it becomes a little more realistic for them when they see me or see one of our friends get hurt,” Barber said. “But we just have to work through it.”

SWAT Responses 2018-2022

Duty, safety and service

Despite being able to discuss tough situations with their families, fellow officers and the department psychologist, there are still incidents that have lasting effects on officers. For many officers, it is when children are involved or end up passing away.

“When I see someone my child's age, you know, pass away from something, that's something that hits really close,” Barber said. “And you try not to put yourself or your kid in that situation, … but that's difficult as a parent. You try to not let it bother you, but it's going to bother you.”

It is in these moments that officers strive to contain their emotions and balance compassion because they believe it is their duty to be resolute and enduring. They cope with the situations they are faced with by focusing on what they need to do for the family in that moment.

“That’s what’s tough,” Barber said. “Everybody is crying around you, and everybody is emotionally bawling, and you're there, kind of having to be the rock.”

Beyond the scene and situation, Burch augmented this thought process.

“For better or worse, I’ve been equipped with the mental fortitude and the physical ability to do these things,” Burch said. “And I would like to be able to do them so that my family doesn't have to deal with this stuff.

"Because as much as I'd like to say it's all rainbows and unicorns, that isn’t the world that we live in. But if my kids think that it is, I'm okay with that because that means I'm doing my job because they're not having to deal with it.”

Undeterred by the effects on their personal lives, members of the FCPS SWAT team joined to step between those intending to do harm and those who may be harmed, Haugo said. Though, like any profession, there are those within policing who do not live up to the communities' or departments' expectations. There are some who have racist beliefs and take advantage of their position, Haugo acknowledged.

“Guess who goes and catches them and puts them in jail?” Haugo said. “We do. Guess who despises them equally or more than anybody else? We do — because it is disgusting to us that they devalue what we do by doing that kind of crap. That makes me furious.”

Those who do live up to the FCPS motto of “safety and service of all” are christened onto the team with a pin, a new rifle and a challenge coin with a depiction of Saint Michael and the words “Sacrifice, Work, Attitude and Team” engraved on it. For those who have put in the work and proved themselves, that is what it means to be a SWAT officer. It doesn’t matter who the caller is.

“When it comes down to it, when (a community member) picks up that phone, (the) one thing there is going to be certainty about is that we’re going to be there,” Barber said. “And there is no disputing that because we will never not come.”